If you are on the carnivore diet, your fiber intake is zero because fiber is unique to plant food. Yet, the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends a daily intake of fiber in the range from 22g to 34g depending on age group and gender. So what should you do? Do you really need fiber on the carnivore diet? I’ve done some extensive research on this topic and here is a short answer that may shock some of you. [1]

You don’t need fiber on the carnivore diet because it has absolutely no nutritional value. Based on available evidence, fiber does not improve bowel function or provide any proven health benefits. In contrast, eliminating fiber has actually been found to be beneficial with secretion.

Read on to find out about all the startling truths and damaging myths about fiber.

What is fiber?

According to the American Association of Cereal Chemists, fiber is “the edible parts of plants or analogues carbohydrates that are resistant to digestion and absorption in the human small intestine with complete or partial fermentation in the large intestine”. [2]

In simple terms, fiber is the indigestible part of the foods that you eat. Think wheat bran, cinnamon bark, tomato skin, and rhubarb stalk skin.

There are a few ways to categorize fiber:

- ‘endogenous‘ and ‘added’ fiber‘. Endogenous fiber is present in the original food matrix whereas added fiber is the fiber obtained from an extraction process and then added to a food product.[3] Due to the perceived health benefit of fiber, it has been added to processed foods or sold as a supplement (e.g. psyllium).

- ‘soluble fiber‘ and ‘insoluble fiber‘. Soluble fiber dissolves in water and can be found in many foods such as oatmeal, nuts, beans, lentils, apples, and blueberries. Insoluble fiber does not dissolve in water and can be found in foods such as wheat, whole wheat bread, whole grain couscous, brown rice, legumes, carrots, cucumbers, and tomatoes. [4]

- ‘fermentable fiber‘ and ‘non-fermentable fiber‘. Fermentable fiber can be readily metabolized by the gut bacteria that normally colonize the large intestine, resulting in the formation of short-chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) and gases. Non-fermentable fiber is resistant to fermentation, i.e. not broken down by gut bacteria.[5]

Do you really need fiber on the carnivore diet?

A review of available evidence shows that you don’t need fiber on the carnivore diet or on any other diets for that matter because there is no evidence of its health benefits. In particular:

- Fiber has no nutritional value

- Fiber doesn’t help with bowel function

- Claims of fiber health benefits are based on epidemiological studies

- Controlled trials do not show protective effects of fiber

- Eliminating fiber is found to be beneficial.

1. Fiber has no nutritional value

Fiber comes from the plant cell walls that provide shapes and architectural supports for the plants. It is unique to plants and doesn’t exist in the human body.[6, 7]

Fiber has zero protein, fat, vitamin or mineral that your body needs. It can’t be digested by your body and is ultimately excreted.

Dr Tan and Seow-Choen, in a 2007 editorial for World Journal of Gastroenterology, call fiber “the ultimate junk food. It is neither digestible nor absorbable and therefore devoid of nutrition. People who ingest fiber are ingesting them to make faeces only“.[8]

2. Fiber doesn’t improve bowel function

A higher fiber intake will logically result in an increased frequency of evacuation. This creates the fallacy that fiber helps with bowel movement. However, in reality, dietary fiber is not found to improve bowel function. In contrast, evidence shows that constipation is actually resolved with the reduction of fiber intake.

Higher plant food intake associates with increased stool frequency

In a review of literature on the characterization of feces and urine by Rose et al (2015),[9] it is shown that a higher plant food intake generally corresponds with higher fiber intake, higher fecal mass, and higher stool frequency. The amount of fiber intake by people following a vegan or vegetarian diet can be 3 to 4 times the amount of fiber intake by people following a high meat diet.

This is obviously just common sense, the more indigestible matter you consume, the more it needs to be excreted.

However, this perhaps leads to the subsequent misleading inference that fiber increases stool frequency, therefore fiber must help with bowel function. Research evidence, nevertheless, shows that it turns out not to be the case.

Increased stool frequency does not mean improved bowel function

In a meta-analysis on the effect of dietary fiber on constipation, Yang et al (2012) conclude that “Dietary fiber intake can obviously increase stool frequency in patients with constipation. It does not obviously improve stool consistency, treatment success, laxative use and painful defecation“. [10]

3. Claims of fiber benefits are based on epidemiological studies

Claims of fiber benefits are based on epidemiological studies

Claims of health benefits of fiber are generally based on results of epidemiological studies which show an inverse relationship between fiber intake and risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and some gastrointestinal diseases. [11, 12, 13, 14]

However, epidemiological studies generally are observational studies that can only show association and can not prove cause and effect.

Problems with epidemiological studies [15, 16]

What is an epidemiological study?

In an epidemiological study, researchers first observe a possible association between a disease and exposure, form a hypothesis about a possible relationship, and then test the hypothesis.

Consider, for example, researchers may observe that people who are on a high fiber diet appear to be more healthy and don’t seem to develop bowel cancer as much as people who follow a low fiber diet. They then form a hypothesis that fiber reduces the risk of cancer and seek to test this hypothesis.

A controlled trial

The researchers could test the above hypothesis through a controlled trial in which one group of participants would follow a high fiber diet and another group of participants would follow a low fiber diet. However, this type of controlled trial is extremely hard, if not impossible, to carry out for a number of reasons:

- Firstly, the researchers would need to recruit a large enough number of people (e.g. a few thousand) to participate to be able to produce meaningful results.

- Secondly, the participants would need to stay on these diets for long enough, like 20 to 30 years, to be able to prove any causation.

- Thirdly, unless they can put all the participants in a lab setting where their fiber intake is controlled, it is unlikely that the participants would actually follow instructions and stay with their respective diets for the entire study period.

- Lastly, there is a huge ethical issue involved. If they turn out to be right, the researchers have knowingly exposed a large number of people to increased cancer risk.

A cohort study

In reality, what researchers would usually have to do is to collect dietary and other lifestyle data from participants using interviews or surveys such as food frequency questionnaires (FFQs).

Unfortunately, data quality is a big issue here. FFQs would typically ask participants questions like the types of foods they eat, the usual frequency of intake, and portion size over a previous period, e.g. week, one month, six months or 12 months. This is subject to considerable measurement error, recall bias, and recall failure, especially when a long recall period is specified. Poor quality data input inevitably produces unreliable results. This is a classic case of rubbish in, rubbish out.

This type of study is also likely to suffer from healthy user bias. For example, participants who have higher fiber intake may be more likely to follow dietary advice, have a healthier lifestyle, be more physically active and have a higher social-economic status than participants who are on a low fiber diet.

Furthermore, given the observational nature of these studies, they can not prove cause and effect and can only report association, for example, between fiber intake and cancer risk.

This is why you need to be extremely cautious when interpreting findings from epidemiological studies.

An example of flawed epidemiological studies

A recently published study by Hullings et al (2020) finds “an inverse association for intake of whole grains … but not dietary fiber …. with colorectal cancer incidence. Intake of whole grains was inversely associated with all colorectal cancer subsites … Fiber from grains, but not other sources, was associated with lower incidence of colorectal cancer …” [17]

This is a typical epidemiological study. The researchers gathered data using a self-administered food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). The FFQ asked participants to provide information on the usual frequency of intake and portion size over the previous 12 months. As discussed above, this method is known to be prone to measurement error, recall bias, and recall failure, especially with such a long recall period of 12 months.

I don’t know about you but it is already difficult for me to recall what I ate last week, let alone over the last 12 months.

In contrast to the above finding, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Asano and Mcleod (2002), involving five randomized control trials with 4,349 subjects, finds that “there is currently no evidence from randomized control trials to suggest that increased dietary fiber intake will reduce the incidence or recurrence of adenomatous polyps within a two to four year period.”[18]

Furthermore, an extensive review of relevant literature to date by Tan and Choen (2007) concludes that “a strong recommendation cannot be made for a protective effect of dietary fiber against colorectal polyp or cancer“.[19]

4. Controlled trials do not show protective effects of fiber

In a number of controlled trials, fiber is not found to provide protective benefits.

In a double-blind clinical trial in which 1,208 participants were randomized to a cereal fiber supplement, Jacobs et al (2002) find that “neither fiber intake from a wheat bran supplement nor total fiber intake affects the recurrence of colorectal adenomas, thus lending further evidence to the body of literature indicating that consumption of a high-fiber diet, especially one rich in cereal fiber, does not reduce the risk of colorectal adenoma recurrence.”[19]

In a randomized trial involving 1,303 participants who were randomly assigned to a high-fiber group and a low-fiber group, Alberts et al (2000) find that “a dietary supplement of wheat-bran fiber does not protect against recurrent colorectal adenomas.” [20]

A randomized control trial involving 110 participants by Chen et al (2006) reports that “our study does not support the hypothesis that water-soluble fiber intake from oat bran reduces total and LDL-cholesterol in study participants with a normal serum cholesterol level”. [21]

In a controlled feeding study of 43 healthy men aged 19-56 to evaluate the effects of fat and fiber consumption on plasma and urine sex hormones in men, Dorgan et al (1996) find that mean plasma concentrations of total and sex-hormone-binding-globulin testosterone were 13% and 15% higher respectively, on the high-fat, low-fiber diet.[22]

A randomized control trial of 88 omnivores by Margetts et al (1988) find that “there was no consistent effect of change in dietary fiber intake on group mean systoloic or diastolic blood pressures“.[23]

5. Eliminating fiber is found to be beneficial

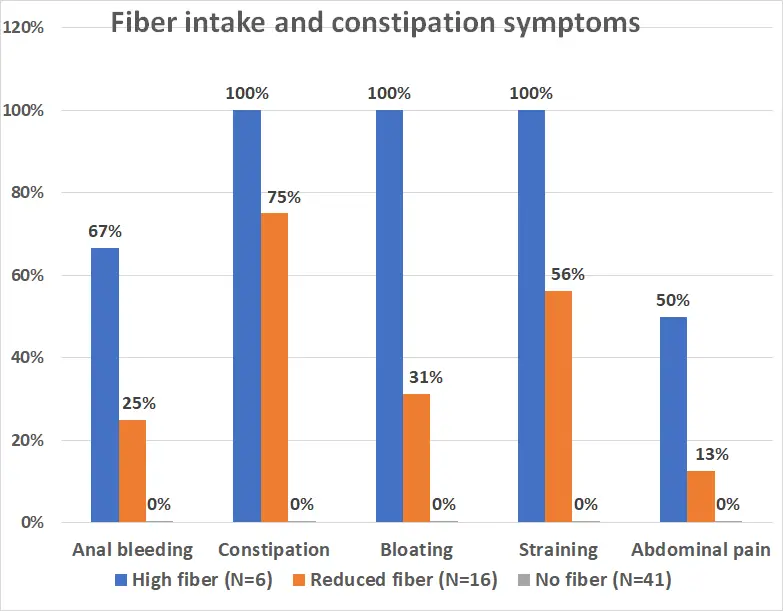

In a remarkable study by Ho et al (2012)[24] published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, 63 patients with idiopathic constipation condition were put on a no fiber diet for two weeks. Thereafter, the patients were asked to reduce the amount of dietary fiber intake to a level that they found acceptable.

At six months, 41 patients who remained on a no fiber diet no longer suffered from constipation, bloating, straining, pain and bleeding.

In contrast, the 6 patients who chose to stay on a high fiber diet still had all of these symptoms.

The 16 patients who were on a reduced fiber diet experienced some improvements accordingly.

This finding flies in the face of medical professionals’ recommendation to include fiber in one’s diet that has been around in the last few decades. [25, 26, 27, 28]

Conclusion

Based on currently available evidence, you clearly don’t need fiber on the carnivore diet.

Tan and Seow-Choen, in a 2007 editorial titled “Fiber and colorectal diseases: Separating fact from fiction” for World Journal of Gastroenterology, conclude that:[29]

… What we have all been made to believe about fiber needs a second look. We often choose to believe a lie, as a lie repeated often enough by enough people becomes accepted as the truth…

The above are facts and myths about fiber. To fiber or not to fiber, it’s your choice.

Disclaimer: The information in this post is for reference purposes only and not intended to constitute or replace professional medical advice. Please consult a qualified medical professional before making any changes to your diet or lifestyle.