There is no doubt that salt and its sodium and chloride content are essential for health. However, there is currently no consensus as to how much salt is adequate. On the carnivore diet, some people are of the view that liberal use of salt is necessary while others reportedly can do with little or no salt at all.

In this post, we will look at why we need salt, how salt requirement varies according to diet and various other factors, whether high salt intake actually causes health problems, whether you need salt on the carnivore diet, and if so how much is adequate.

Content

- Why you need salt

- How salt balance is maintained

- How much salt do you need?

- Risks of high and low salt intake

- How much salt did our ancestors eat?

- Do you need salt on the carnivore diet?

- Conclusion

Why you need salt

The salt you add to your food is sodium chloride (NaCl), a naturally occurring mineral, which contains 40% sodium and 60% chloride.

Sodium is one of the body’s electrolytes which carries an electric charge when dissolved in body fluids such as blood. Most of the body’s sodium is located in the blood and in the fluid around cells. Sodium helps the body keep fluids in a normal balance and maintain blood pressure. In addition, sodium plays a key role in normal nerve and muscle function. [1]

Chloride is also an important electrolyte that helps regulate body fluids, keeping electrolyte balance, preserving electrical neutrality, and maintaining the pH of the body fluids.[2, 3]

Both sodium and chloride are essential for the proper functioning of your body. Your body can’t make them and must get them from food and drinks. Both sodium and chloride can be found in animal and plant food in small quantities. They are excreted through urine and sweat. [4, 5]

How salt balance is maintained

In healthy individuals, the blood sodium level is tightly controlled and maintained in a narrow range of 137 to 142 milliequivalents per liter (mEq/L) of plasma. Meanwhile, normal serum chloride concentrations are in the range from 96 to 106 mEq/L. [6, 7]

Your body works to maintain this normal level of salt (sodium and chloride) in the blood through two mechanisms, thirst and antidiuretic hormone release. [8, 9]

If you eat something salty and raise the level of salt in the blood, you will feel thirsty and must drink water, hence bringing the salt level in the blood down. However, the kidneys will work to increase the excretion through urine and return blood and salt level back to normal.

If the salt level is too low, for example, due to excessive sweat through prolonged physical exertion, the antidiuretic hormone is released and the kidneys will work to retain salt and conserve water.

In fact, your body is so good at maintaining a normal level of sodium and other electrolytes in the blood that the fluctuations in dietary intake don’t have any material impact on their serum levels unless your kidneys or senses are significantly impaired in some way.[10]

How much salt do you need?

Determinants of your salt need

Your salt requirement depends on many factors such as body size, diet, the level of physical activities, climate, and health conditions.

Obviously, the bigger and the more physically active you are, the higher your salt need will be. Endurance athletes can lose a substantial amount of sodium and water during training and competition. If they don’t replenish accordingly, they are at risk of fatigue, sub-optimal performance, muscle cramps, and poor recovery. More serious risks include confusion, seizures, unconsciousness, and even death.

Heat, humidity, and the degree of acclimatization also affect your salt requirement. You are likely to sweat more in a hot and humid environment and, as a result, lose more salt through sweat. However, the rate of salt loss through sweat varies across individuals, and the need to replenish therefore can differ greatly.

In addition, the specifics of your diet can influence your salt requirement.

For example, if your diet is high in carbohydrates, your sodium need will increase. This is because once carbohydrates are broken down into sugar, absorptive cells in the small intestine need sodium in order to transport the sugar from your gut to your bloodstream. If you don’t eat a lot of carbs or go zero carbs, your salt or sodium requirement will definitely be less.

People who have a potassium-rich diet can handle more salt than otherwise. Potassium is another important electrolyte that your body needs and the normal ratio between potassium and sodium is about 3 to 1. Eating food high in potassium can help your body excrete more sodium.

Caffeinated drinks such as coffee, tea, and sports drinks can also increase your salt requirement. For example, if you drink 4 cups of coffee a day, you lose about a half teaspoon of salt or about 1,200 mg of sodium, according to Dr. James DiNicolantonio. Hence, all else constant, coffee drinkers will need more salt than non-coffee drinkers.

Current salt intake recommendations

The current salt intake recommendations vary greatly across health authorities.

1.The National Academy of Medicine[11]

Due to insufficient data available, the National Academy of Medicine does not issue a Recommended Dietary Allowance but established an Adequate Intake for sodium as follows:

- 19-50 years: 1.5 g (65 mmol)/day

- 51-70 years: 1.3 g (55 mmol)/day

- >70 years old: 1.2 g (50mmol)/day.

This intake level does not apply to individuals who lose large volumes of sodium in sweat, such as competitive athletes and workers exposed to extreme heat stress (e.g., foundry workers and firefighters).

The Adequate Intake for chloride is as follows:

- 19-50 years: 2.3 g (65 mmol)/day

- 51-70 years: 2.0 g (55 mmol)/day

- >70 years: 1.8 g (50 mmol)/day.

In summary, the average adult should aim for 1.5 grams of sodium and 2.3 grams of chloride a day. This is equivalent to 3.8 grams or 2/3 of a teaspoon of salt a day.

2. USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025[12]

Citing the high intake of sodium across the U.S. population of 2g to 5g per day and the evidence on the benefit of reducing sodium intake on cardiovascular risk and hypertension risk, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025 encourage Americans to reduce sodium intake and consume less salt.

It recommends a sodium intake of less than 2.3 grams per day and even less for children younger than age 14. This is equivalent to 5.8 grams or one teaspoon of salt a day.

3. The UK government[13]

The UK Government is of the view that a diet high in salt or sodium can cause raised blood pressure, which can increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

It recommends adults and children aged 11 years and over should have no more than 2.4g sodium or 6g salt per day. This is about one teaspoon a day.

4. The World Health Organization[14]

The World Health Organization is of the view that high sodium consumption and insufficient potassium intake contribute to high blood pressure and increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

WHO recommends that adults consume less than 5g or just under a teaspoon of salt per day. This should be adjusted downward for children aged 2 to 15 years based on their energy requirements relative to those of adults.

Risks of high and low salt intake

As can be seen above, the current consensus view of health authorities worldwide seems to be that we should limit salt consumption to about one teaspoon a day or less due to the perceived health risks associated with high salt consumption.

We will have a look at the evidence below to see whether the fear of salt is actually backed by quality evidence.

Randomized controlled trials

(i) Midgley et al (1996)[15]

In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials covering 56 trials with 3,505 participants, it was found that salt reduction had no benefit for people with normal blood pressure and but had a small benefit for older people with high blood pressure (3.7 mm Hg for systolic and 0.9 mm Hg for diastolic).

The authors concluded that evidence does not support universal salt restriction recommendations.

(ii) Sacks et al (2001)[16]

In this study, a total of 412 participants were randomly assigned to eat either a control diet typical of intake in the United States or the DASH diet. Within the assigned diet, participants ate foods with high, intermediate, and low levels of sodium for 30 consecutive days each.

On the standard American diet:

- reducing the sodium intake from high to intermediate levels reducing the systolic blood pressure by 2.1 mm Hg

- reducing the sodium intake from intermediate level to low level causing an additional reduction of 4.6 mm Hg

On the DASH diet:

- reducing the sodium intake from high to intermediate levels reducing the systolic blood pressure by 1.3 mm Hg

- reducing the sodium intake from intermediate level to low level causing an additional reduction of 1.7 mm Hg.

The finding of this study is often quoted in support of low sodium intake advice by authorities.

(iii) Adler et al (2014)[17]

In this meta-analysis of 8 randomized controlled trials with 7,284 participants, the authors found that a reduction in salt consumption led to a small reduction in blood pressure after 6 months.

In particular, for people with normal blood pressure, there was a reduction of 2.32 mm Hg for systolic and 0.8 for diastolic. For people with high blood pressure, there was a reduction of 4.14mm Hg for systolic but no difference in diastolic blood pressure.

There was no evidence of a reduction in all-cause mortality. There was weak evidence of cardiovascular benefits but these findings were inconclusive and were driven by a single trial among retirement home residents.

(iv) Khan et al (2019)[18]

This study is a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses of RCTs that assessed the effects of nutritional supplements or dietary interventions on all-cause mortality or cardiovascular outcomes, such as death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary heart disease.

The authors concluded that there was moderate-certainty evidence that reduced salt intake decreased the risk for all-cause mortality in people with normal blood pressure and cardiovascular mortality in people with high blood pressure. The authors also noted a limitation of the study is the suboptimal quality and certainty of evidence.

Epidemiological studies

(i) O’Donnell et al (2014)[19]

In a study involving 101,945 participants in 17 countries, sodium intake was estimated from urine samples and the composite outcome of death and major cardiovascular events were followed up after 3.7 years.

It was found that an estimated sodium intake between 3 and 6 g per day was associated with a lower risk of death and cardiovascular events than was either a higher or lower estimated level of intake.

This range of sodium intake is 2 to 4 times what the Institute of Medicine recommends.

(ii) Mente et al (2016)[20]

In a pooled analysis of studies comprising 133,118 from 49 countries, the authors examined the relationship between urinary sodium excretion (a proxy for sodium intake) and the composite outcome of death and major cardiovascular disease events over a median of 4.2 years and blood pressure.

The main findings of the study are:

- For people with high blood pressure, consuming sodium of more than 7g a day or less than 3g a day were both associated with an increased risk of death and cardiovascular disease compared to people consuming from 4 to 5 grams a day

- For people with normal blood pressure, consuming sodium of more than 7g a day was not associated with an increased risk of death and cardiovascular disease, but consuming sodium of less than 3g a day was associated with a significantly increased risk of death and cardiovascular disease.

- Furthermore, irrespective of blood pressure status, people consuming less sodium (< 3g a day) actually had worse health outcomes compared to people consuming more sodium (>7g a day).

In layman’s terms, according to this study:

- Whether you have or don’t have high blood pressure, consuming too little salt (less than 3 grams of sodium a day or less than 1⅓ teaspoon of salt a day) increases your risk of death and cardiovascular diseases

- If you have normal blood pressure, consuming a lot of sodium (more than 7g a day or more than 3 teaspoons of salt a day) doesn’t seem to do you any harm

- If you have high blood pressure, it’s better to limit sodium consumption to 4 to 5 grams a day or about 2 teaspoons of salt a day. This is double the current salt intake recommendation.

(iii) O’Donnell et al (2020)[21]

In a comprehensive review of evidence to date, the authors contend that current evidence suggests that most of the world’s population consumes a moderate amount of sodium (2.3g – 4.6g/day or 1–2 teaspoons/day). This level of consumption is not associated with increased cardiovascular risk and the risk of cardiovascular disease only increases when sodium intakes exceed 5 g/day.

(iv) Messerli (2021)[22]

In this large-scale epidemiological study, the authors examined the relation between sodium intake and life expectancy as well as survival in 181 countries worldwide.

Contrary to the advice from health authorities and organizations worldwide, they found a positive correlation between sodium intake and life expectancy at birth and at age of 60.

In particular, there was an increase of 2.6 years of healthy life expectancy at birth and an additional 0.3 years at the age of 60 for each additional gram of daily sodium intake.

In addition, all-cause mortality was found to be inversely correlated with sodium intake with 131 fewer deaths per each additional gram of daily sodium intake.

In a sensitivity analysis restricted to 46 countries in the highest income class, sodium intake continued to correlate positively with healthy life expectancy at birth (an increase of 3.4 years of healthy life expectancy at birth for each additional gram of daily sodium intake) and all-cause mortality (168 fewer deaths for each additional gram of daily sodium intake).

Summary of evidence

In summary, in randomized controlled trials, the reduction of sodium intake is found to modestly lower blood pressure from 1.3 to 4.6 mmHg. This is a negligible impact in the whole scheme of things, for example when high blood pressure is from 140 mmHg and above. However, there is no strong evidence indicating that lowering salt intake leads to a decrease in mortality and cardiovascular risks.

In epidemiological studies, overall findings indicate that 3 to 6g of sodium a day is positively associated with better health outcomes. This level of sodium consumption, however, is 2 to 4 times the currently recommended level. Also, note that due to the observational nature of epidemiological studies, no causality can be proven.

At best, the totality of evidence suggests that for people with high blood pressure, there is some benefit in maintaining a moderate salt consumption.

As for the general population, there is no strong evidence suggesting that they should limit their salt consumption.

In my view, it is pretty reckless to universally recommend over 6 billion people to limit salt consumption on such flimsy evidence which is mostly centered around a single trial of 412 people over a 30-day period.

How much salt did our ancestors eat?

As can be seen from above, even the Institute of Medicine hasn’t been able to establish a Recommended Dietary Allowance for salt consumption and issued an adequate intake guideline instead.

In addition, the universal salt reduction recommendation appears to be based on very weak evidence.

In this section, we will look at whether salt was a prominent feature in our ancestors’ diet and if so how much they actually used.

Prehistoric humans

This is no reported evidence indicating that our human ancestors extracted salt, traded salt, or added salt to their diet. They got all the minerals and other nutrients from their diet which was mostly meat.[23]

Humans only began to search for salt and came to value it with the transition from living off the land via hunting and gathering to subsisting on agricultural produces.

So how much salt did our human ancestors get from their diet?

In a study that reconstructed the paleolithic diet using wild games and uncultivated vegetable foods, Easton et al (1997) estimated that preagricultural humans consumed only 768 mg of sodium daily. This is equivalent to about 2 grams or about 1/3 teaspoon of salt.[24]

However, note that this is probably a very rough estimate only because in this study the paleolithic diet is constructed based on recent hunter-gatherer societies’ diets. In particular, the authors used a micro-nutrition composition consisting of 37% protein, 41% carbohydrates, and 22% fat.

While this might be the typical diet of recent hunter-gatherer groups, it is unlikely to be a good representative of our ancestors’ diet because the ecosystem of the 20th century hunter-gatherer societies is totally different from the ecosystem that existed 2 million years ago.[25]

The totality of evidence shows that humans were definitely not generalist omnivores as previously widely believed. Instead, they were hyper-carnivorous apex predators that ate mostly meat from large animals for 2 million years. Their diet was definitely not that of typical hunter-gatherer societies and it is highly unlikely that they would have gotten 41% of their energy from carbohydrate sources. [26]

No salt, low salt and high salt groups

There were some groups who followed traditional meat-based diets like the Eskimos and the Maasai and some of the northwest American Indians did not add salt to their food. The estimated salt content in their food is from less than 1 gram to a maximum of 5 grams a day.[27]

Vilhjalmur Stefansson, an Arctic explorer and anthropologist, spent cumulatively about 5 years eating meat only with the Eskimos between 1906 and 1918. The Eskimos didn’t use salt and disliked salt. Stefansson recalled from his study that “in pre-Columbian times salt was unknown or the taste of it disliked and the use of it avoided through much of North and South America.” Living with the Eskimos, he came to realize that salt was more of a custom than a necessity and, after a few months, could do without salt and didn’t miss it at all.[28]

However, there are also some groups who add salt liberally to their diet and consume a large amount of salt daily (many times the current recommendation) as can be seen in the table below.

This clearly demonstrates humans’ amazing ability to live with a very low salt intake (1g a day) or very high salt intake (55g a day).

Do you need salt on the carnivore diet?

Based on available evidence, it appears that you don’t need to add salt to the carnivore diet because animal-sourced food contains sufficient levels of sodium, chloride, and potassium to meet your body’s needs. However, if you feel like using salt on the carnivore diet, add it to suit your personal preference. There is insufficient evidence indicating that salt intake above the current recommended level increases health risks.

Carnivore diet meals contain sufficient sodium

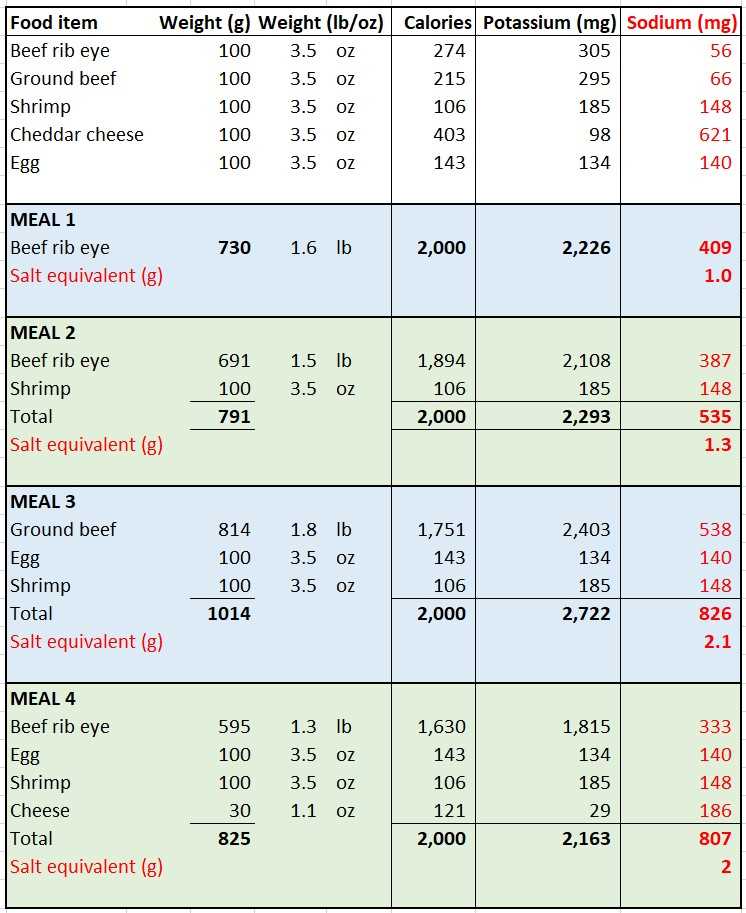

In the table below, I have constructed several carnivore diet meals using carnivore diet staple food items to deliver 2,000 calories a day.

As can be seen in the table, these meals provide 409mg to 826mg of sodium which is equivalent to sodium in 1g to 2g of salt.

If you eat rib-eye steak all day, you will have consumed about 400mg of sodium or about 1g of equivalent salt a day.

If you eat mostly meat and a bit of egg, seafood, and cheese, you will get about 2g of equivalent salt a day.

This is a very low sodium intake and much lower than the current upper intake recommendation. However, as mentioned above, our ancestors did not use salt, and groups that are on a meat-based diet do not have the habit of adding salt to their food.

So, it is certainly possible to live on the carnivore diet without additional salt as many people on this diet have found. Not only do you get sodium from meat, but you also get chloride and potassium, all in a perfect ratio as nature intended.

When you consume a lot of carbohydrates, you will need more salt because sodium is needed for glucose absorption. But when you are on the carnivore diet, there is a very little amount of carbohydrates, your salt requirement will reduce accordingly.

Having said that, please feel free to use salt on the carnivore diet to suit your personal taste because as you can see from the evidence presented above, there is no strong evidence against high salt consumption. If you happen to use too much salt, your body has the ability to self-regulate the sodium and keep an overall electrolyte balance. Extra sodium will be excreted.

However, there might be some risks associated with too little salt consumption. If you consume too little sodium that is insufficient to meet your body’s needs, and because your body can’t make extra sodium itself and there would be risks like confusion, twitches, seizures, unresponsiveness, and potentially death.

I would rather take the risk of having too much salt and let my body work out the right balance than having too little salt and suffering the consequences.

Furthermore, people’s salt requirements also vary significantly due to differences in body size, diet, level of physical activities, climate, and health status, it is impossible to set a goal or a limit for salt intake. So, it makes sense to just let your body be the guide.

Despite the ongoing advice to reduce salt intake, the average global salt consumption has not changed much over time. So, it is certainly possible that people have been very good at self-regulating their salt consumption.[30]

Personally, without trying, I found myself using less and less salt as my body becomes more adapted to this way of eating. I no longer put salt in bone broth, add only a pinch of salt to steak and eggs, and sometimes use no salt at all.

If you use salt, any salt will do as long as it doesn’t have any additives or anti-caking agents.

Conclusion

The salt debate is still going and salt appears to be a complex topic but perhaps it shouldn’t haven’t been made that complicated.

Your body needs sodium and chloride. How much it needs depends on your diet and other factors.

Animal foods have both sodium and chloride (even though the USDA doesn’t list the chloride content of foods).

There is no evidence that our ancestors added salt to their food. A number of groups following traditional diets also didn’t use salt.

However, the risk of not having enough salt would outweigh the risk of having too much salt because while your body can excrete extra sodium, it can’t make this essential electrolyte.

Furthermore, we now live in an environment that is very different from the one that our ancestors used to live in. Our food is also very different from what our ancestors used to eat.

So, the best thing it would seem is to listen to your body and add salt or stay away from salt the way your body tells you. Some people on the carnivore diet reported feeling better without salt and you might find the same as you become fully adapted to this diet. But everybody is different. If you exercise a lot or tend to sweat a lot, you may need to add salt regularly to your food.

I hope you find this post useful. Please check out my library of articles on the carnivore diet here which is updated regularly.

Disclaimer: The information in this post is for reference purposes only and not intended to constitute or replace professional medical advice. Please consult a qualified medical professional before making any changes to your diet or lifestyle.